Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye argued that where you are is as important as who you are. Just as one affects their environment, people are, in turn, affected by those same surroundings. The Romantic poets located this exchange in nature, turning their work toward subjects ruminating on not only their own individuality, but the natural world in which that rumination occurred. It is therefore only logical, in the highly commercial, Capitalist late 20th and early 21st Century United States, that this symbiosis of person and place can be housed, at least for some, in the malls and chain stores freckled across the American landscape.

For me, this was Toys “R” Us. It has been a permanent fixture throughout my 32 years, just as it’s been for the lives of many of my Millennial peers. In light of last week’s announcement that the chain will be going out of business, much is being reported about the people who made, and ultimately eroded, this place—but there’s much more to be said about the place that made the people. The Toys “R” Us Kids. Those for whom the place precedes the person.

From its birth, Toys “R” Us has represented a fusion of person and place. When Charles P. Lazarus founded the chain in 1957, the name Toys “R” Us originated as a linguistic play on his last name—but “Lazarus” and “Toys R Us” do more than rhyme. They announce both a location and a family legacy, meant to invite the customer to unite their real family with Lazarus’ imagined one. After all, the childish backwards “R” was there from the beginning, giving visitors the illusion that an actual child was behind the whole enterprise, scribbling the brand name on countless signs and advertisements. Lazarus’ previous venture, the kids’ furniture store Children’s Bargain Town, couldn’t hold a candle to that kind of personality.

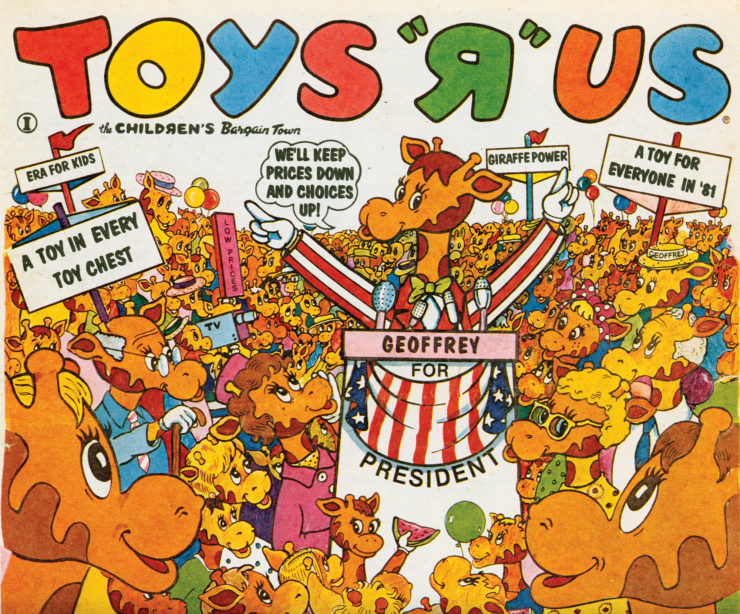

However, the personhood of this place was artificial, as corporations are not, as certain politicians would have you believe, people. A child didn’t write the store’s sign; Charles Lazarus was not, at least literally, Toys “R” Us. In order for a store to become as cathartic an experience as Wordsworth’s Westminster Bridge, it needed the people that visited to see themselves as not only customers, but residents of its imaginary land. To that end, by 1965, Toys “R” Us retooled Dr. G. Raffe, the old Children’s Bargain Town mascot, into a new anthropomorphic giraffe named “Geoffrey” by a store sales associate. In 1973, Geoffrey appeared in a commercial featuring numerous excited children dancing alongside their new friend, merging the store’s target audience with the its own fantasy world that seemed to be, at least for a moment on TV, as real as anything else. By 1981, Geoffrey was running for President in Toys “R” Us print ads under slogans like “Era for Kids” and “A Toy in Every Toy Chest.” In the ads, Geoffrey clearly had a lot of support from his cartoon giraffe base, but the ads also drew kids into this new country where they, too, were to wield some undefined power in the new “Era” Geoffrey was to usher in.

Since kids didn’t actually have this much agency in reality, of course, Lazarus understood that bringing parents into stores was key. During Toys “R” Us’ steady ascent in the pre-dot-com 1970s and ’80s, Lazarus used off-price positioning, or the selling of key items at below-cost in hopes of driving up impulse buys, to his advantage. For example, Toys “R” Us sold diapers for less than they paid for them, with the idea that parents would purchase other goods spontaneously on-site. The strategy worked, and it furthered the image of Toys “R” Us as more than just a store, but a place that understood. It understood parenting. It understood the need for low-priced essentials. It understood kids. It is William Wordsworth’s rainbow in “My Heart Leaps Up,” forever linked to his speaker’s humanity, his insistent desire to carry the joy and enthusiasm of childhood through to adulthood and later life.

It will be obvious by now that I am speaking about Toys “R” Us romantically, in every sense of the word. I use capital-R Romanticism because Toys “R” Us was a place that, in all of the above ways, walked with the individual, providing a kid’s version of a space in which emotion can be spontaneously felt. I use lower case-r romantic language because this is, in addition to a brief cultural history and lyric essay, a love letter, however absurd that may sound. I’m taking this moment to revel in a kind of backwards-“R” “R”omanticism, because that may be the best representation of what that reverse “R” in Toys “R” Us truly stands for: spontaneous, semi-Romantic childhood emotion that finds parallels in the magical, pseudo-natural aisles of a toy store. The child’s version of R/r/”R”omance is at once misplaced and wonderfully playful.

In order to do this, though, I recognize that I am ignoring plenty. I’m ignoring any employee who was underpayed or underserved by this company. I’m ignoring business practices that may or may not have been sound. I’m ignoring the all-around underbelly of the toy industry that includes horrible treatment of Chinese laborers and unfathomable pollution of rivers and groundwater. And what about the immense privilege it takes to locate such integral feelings of happiness within a store, an experience whose use is defined, at least partly, by money? I know that all of these are scandals of the Geoffrey administration, but what am I supposed to do? I helped elect a cartoon giraffe as the President of my imagination.

I became a Toys “R” Us kid when the brand was booming, around 1989. My first living memories include trips to the Knoxville, Tennessee Toys “R” Us for 3.75-inch G.I. Joes and assorted Lego sets. Its supermarket-like layout is seared into my brain, from the long hallway I meandered down after entering, to the clearing that cultivated displays of that year’s hottest toys, to the aisles arranged in order of: games | outdoor | toy cars | action figures | bikes | dolls | Legos. Much like the hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining, I can’t quite explain how the geography worked, but, unlike The Shining, the store’s twists and turns created a joyful labyrinth of mystery—a place I was delighted to get lost in, a veritable magical forest in which the creatures I stumbled upon happened to resemble my favorite cartoon characters.

This is part of what separates backwards-“R” “R”omanticism from literary Romanticism. The expression of and reflection on feeling at Toys “R” Us does not occur in solitude, as it often does in literary Romanticism. In my case, I was often in the company of the Red Ranger, Earthworm Jim, Storm, Optimus Prime, and, for a deep cut, Super Soakerman. When I asked the college freshmen in my classes about their thoughts on the closure of Toys “R” Us, they, like me, mourned the loss of being surrounded by physical manifestations of their TV, comic book, and video game heroes. Playing in the aisles of Toys “R” Us offered all the thrills of Ready Player One, except without the necessity of plot. The point was simply to encounter, create, and dream.

And, perchance, to buy. As a kid, this is where other humans came in. Though people, namely my mother and grandmother, took me to the store, they could not occupy the playscape I invented once I arrived. Thankfully, though, they were always there when I reemerged, usually box-in-hand. My grandmother immigrated to the United States from Greece in 1951, a refugee from their Civil War. My mom was born in Greece, but fled the same war with her parents and brothers when she was two. I note this to illustrate that hardship juxtaposed with the saccharine and distinctly American Toys “R” Us, and my childhood, and childish, attitude that was totally oblivious to their plight and experiences.

My mom, conditioned to understand money as constantly scarce and rarely used for pleasure, would often, understandably, turn down my pleas for yet another Power Ranger. My grandmother, having survived Nazis and Communists, took a different approach. To her, funding a child’s happiness was a way to reclaim the childhood that was stolen from her, which often meant giving carte blanche at Toys “R” Us. Regardless of these personality differences, though, Toys “R” Us instantly brought me closer to my mom and my grandmother. Bad grades didn’t exist there. The pressures of growing up didn’t exist there; in fact, there was even a theme song that stressed prolonged childhood. All we had were the toys, whether we purchased them or not, and, as we discussed questions like, “What does this do?” and “Who is that?” I began building my own geek identity and sharing it with two of the most unlikely people: adults.

Toys “R” Us would change its layout several times throughout my life, and I came to memorize those maps, too. I had to, if this was to be the home and landscape of my imagination. It was also a point of pride. As a child, at a time when I felt like I wasn’t an expert on anything and still had so much to learn about almost everything, I could feel some sense of mastery over this place. By 1997, I knew it so well, I made myself a life-long Volunteer Toys “R” Us Tour Guide, helping customers find the items they wanted. I was 10.

The only place in the store that was off-limits was “The Back.” When I was a kid, The Back might as well have been the positive version of the Upside Down. Instead of being populated by the Demogorgons of Stranger Things, it held what surely were limitless possibilities, even beyond the wonders that existed on the public pegs of the regular store. Oh, the 12-inch Cyclops toy wasn’t on the shelf? Maybe there was one…in The Back. If you got the right employee, they’d “check.” This probably meant that said clerk went into The Back, stood around for a minute, and then returned with a shrug and a, “Nope, sorry, kid. I looked everywhere, though.” The mystique of The Back was kept alive on rumors. Everyone knew someone who scored the very last available sought-after toy because they found a helpful employee who successfully consulted The Back. I just never had much luck with it, myself. But now, The Back provides me with the only metaphor I’m truly comfortable applying to the future of Toys “R” Us. It isn’t gone; it’s all just in The Back.

When I was 15, we moved from Knoxville, Tennessee, to New York City. That abrupt transition was a lot to bear. When we pulled into our new house in our new neighborhood that Sunday, I looked around for anything familiar. I found nothing. I was supposed to start 10th Grade that Tuesday, which, for a shy teenager like me, was terrifying. Furthermore, that Tuesday, a date that seemed insignificant when we moved in three days earlier, turned out to be 9/11/2001.

The search for anything recognizable in New York City became frantic. The relief I felt upon finding a Toys “R” Us, in Times Square, no less, was like that captured in Wordsworth’s “Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.” It was the type of relief that comes to the rescue, echoing from a distant, joyous place of youth. That Toys “R” Us became more my home than the actual house for which my parents were shelling out a ridiculous amount of money in rent. I skipped gym and math class to spend afternoons with superheroes, and I’m not sorry. The shyness I felt around my peers fell away when I searched through pegs and bins of toys.

There was one particular employee at that Times Square megastore with whom I’d spend a great deal of time discussing life’s real questions: “Is that Darth Maul the rare one?” “Did someone buy the last Deadpool?” and “What’s the deal with Transformers these days?” I’m sure the scholarly part of me that writes about toys was born during those conversations. What’s more, it was those talks that helped me transition out of the shell that had previously kept my geek voice to a whisper. That floor associate will probably never know how important those chats were to me; I just hope he didn’t find me too annoying.

As I moved through college and graduate school and started working professionally as a writer, I’d go to Toys “R” Us just to think, often imagining the toys on the shelves speaking various lines of dialogue or debating ideas. The magic never went away; it just grew with me. My older eyes would see the aisles in new ways. The artificiality of “Girls” and “Boys” sections became more obvious. The absence of female characters on action figure pegs taught me that, though this toy store-based imaginary world was enchanted, it was also unfair. This may be the saddest part of the end of Toys “R” Us as we know it: the fact that, just at the end, these gender imbalances seemed to be in the early stages of being addressed, at long last. Just last week, post-liquidation announcement, my local Toys “R” Us moved the DC Super Hero Girls dolls into the action figure section, commonly thought of as the heart of the “Boys” aisles. There, children of all genders played and compared toys which were, finally, allowed to simply be toys, not feminine “dolls” or masculine “action figures” used to promote adherence to gender stereotypes. I only wish we’d gotten to see more of that world.

This is why the loss of Toys “R” Us is significant. It seemed like Toys “R” Us, for some, would be a permanent place that would foster magic. As Wordsworth writes in his Preface to Lyrical Ballads, in which he defines parameters for literary Romanticism:

The principal object, then, proposed in these Poems was to choose incidents and situations from common life, and to relate or describe them, throughout, as far as was possible in a selection of language really used by men, and, at the same time, to throw over them a certain colouring of imagination, whereby ordinary things should be presented to the mind in an unusual aspect; and, further, and above all, to make these incidents and situations interesting by tracing in them, truly though not ostentatiously, the the primary laws of our nature: chiefly, as far as regards the manner in which we associate ideas in a state of excitement.

Backwards-“R” “R”omanticism at Toys “R” Us holds a simpler version of this true: that the numerous aisles of this toy store laid out a continuum of plastic, plush, and die cast metal, raw materials, and, over them, provided for the “colouring of imagination,” where the ordinary became extraordinary. This permitted kids, and maybe some adults, too, access to a pseudo-imaginary landscape where spontaneous emotion was the point. Months ago at a Toys “R” Us store, I saw a child, probably around nine, push a button on the Jurassic World Dino-Hybrid Indominous Rex toy, unleashing spikes from the back of the plastic lizard. The child’s face lit up with a surprise and delight I think Wordsworth would have immediately recognized. Places that embrace this sort of play and expression are few and far between, and, now, without Toys “R” Us, this “R”omantic map has become notably more sparse.

When I was a kid, I found a Star Wars: Power of the Force Mon Mothma action figure at the Knoxville Toys “R” Us. She was hard to find, and on sale for a strange price, something like $3.24. Knowing I could save her from the grips of the Discount Bin Empire, I quickly hid her in a shadow dimension behind a row of board games no one cared about. I ran to my mom, who was reading at a nearby Barnes & Noble and plead my case. This wasn’t just buying a toy; it was completing an intergalactic mission. She handed me five bucks, seemingly moved by my mini-presentation. Out of breath, I retrieved Mon Mothma from the Boring Board Game Dimension, took her to the cash register, and made the jump to hyperspace, hero of the Rebellion in-hand. That Toys “R” Us, and all the worlds it contained, will close at the end of next month. With it will go the infinitude of pathways to the imaginary, and the impulsive joy that comes with following them.

Thankfully, I still have my Mon Mothma.

Jonathan Alexandratos is a playwright and essayist who writes about action figures and grief. His edited collection of academic essays on toys, Articulating the Action Figure: Essays on the Toys and Their Messages, is out now from McFarland. Find him on Twitter @jalexan.